Types of Fidchell

There is no authoritative, documented history of what Fidchell boards looked like, or exactly how the game was played. People have reconstructed the game in various ways, some more imaginative than others. Some are based on Tafl, or Brandubh, which is not historically accurate, but still enjoyable to play. Others are based on archaeological discoveries, with the rules filled in by deduction. My favorite one is actually a complete fiction, but it works marvelously. Let’s take a look at them.

Many people, and many web sites, class Fidchell as a tafl-based game, with a grid, usually 7X7 squares, having a king in the middle, surrounded by a number of defending pieces and twice that many attackers. The object of the game is to clear a path for the king to the edge of the board by capturing the enemy pieces. This is usually done by flanking them. The attackers try to capture all the defending pieces or create a situation in which it is impossible to create a path for the king.

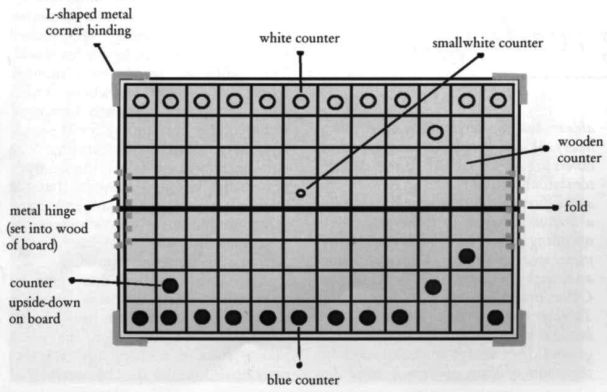

A game board discovered in 1932 at Balinderry, West Meath, Ireland which many have assumed is a Fidchell board.

Much of this is based on the discovery of an ancient game board at Balinderry Ireland in 1932. The board was found during the excavation of a “crannog”, or lake dwelling in West Meath, Ireland. The board is 9.5 inches square and has 7 rows of 7 holes each. The center one is circled as if to set it apart for the king. The border decorations carved into it are similar to those found on the Isle of Man dating from the 10th century AD, which makes its Celtic origins quite clear. This board appears very similar to the Scandinavian Tafl boards and thus very likely related to the Irish game Brandub.

Many people have just automatically assumed that this is a Fidchell board, or have connected it to that game, making Fidchell a variation of Brandub, and related to the Tafl games. The problem is that this board, and those games, do not conform to the descriptions of Fidchell from ancient documents. It is still an ancient Celtic game though, and fun to play.

Another discovery, at Stanway, near Colchester in Essex England in 1996, added fuel for this discussion. It was found in the grave of a Celtic Briton physician, along with his surgical tools. The most dramatic part of this discovery is that the game pieces were on the board and appear to represent a game actually in progress. There has been a lot of speculation about how the game was played, since we have more to go on than in other cases, and the opinion has been voiced that the board was placed there by a friend of the doctor with whom he used to play the game.

This board appears to be eight squares by twelve, with thirteen game pieces on each side. One is much smaller than the rest, but we don’t know if that is significant to the game. The pieces are blue or white glass. Could this have been an ancient Celtic game similar to Fidchell? It’s possible.

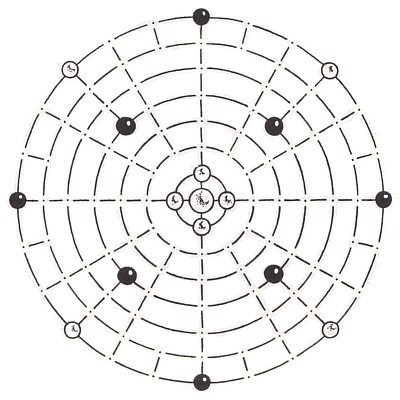

The last major category of Fidchell games was invented by Nigel Suckling from descriptions he found in the tales and folklore of the Celtic people. Since the game is described as having a king in the center and equal numbers of players, he knew it could not be the same as Brandubh. Additionally, there is a corresponding game in Wales called Gwyddbwyll, which also means “wooden wisdom” and seems to share a history with Fidchell. It is clearly separate from Tawlbwrdd, the Welsh version of Brandubh and also a variant of Tafl. This version seems best suited to what we know of Fidchell.

The biggest problem with this is that we have no actual evidence of any board like this, or any descriptions which clearly prove that a game like this was played in ancient times. Nonetheless, it’s my favorite of the bunch, because it seems to so accurately reflect the spirit of the ancient Celts and the magical descriptions of Fidchell.

So which of these is the “real” Fidchell? It’s impossible to answer that question with any authority, given the current evidence. It’s almost certain that the Balinderry board is Brandubh, or some tafl-variant, and not Fidchell, based on the descriptions we have. The Stanway board appears to be from Celtic/Roman Britain, but there’s no documentary evidence to associate it with Fidchell. And despite it’s attractiveness, Suckling made his board out of his imagination. Perhaps archaeologists, or linguists, or folklorists will someday discover the real answer to this question. Meanwhile, we have some great games to play and enjoy, and the tantalizing question of what they meant to the ancient Celts.